|

|

|

Kilns | Car Kiln | Wood Kilns | Pottery Kilns | Paperclay | Fire Trees | Constructs

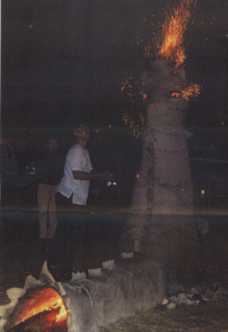

Below: Nakano from the Yamanaka Clay Co. tests

the paperclay with a blow torch.

|

|

Wali Hawes builds paperclay dragons

as part of his life as a potter in Japan

Above: The body of the dragon being constructed using the

coil method. |

Since my days as a student potter, I have always been fascinated

with kilns, especially wood fired and gas kilns. In I986 an incident

took place which sparked off what became Fired Earth Constructions

and, in particular, Fire Trees, Dragons and Fire Flowers. I spent

some time in Navapalos, in the province of Soria, Spain, learning

about adobes and rammed earth. I built a bottle kiln on site out

of adobes to fire some pottery, reaching I000'C in about eight

hours. I noticed that the kiln had fired itself (at least on the

inside) thus converting itself into a ceramic object. I later presented

these 'kilns as objects' at an art show in Barcelona and later

at several festivals and workshops in Spain and England.

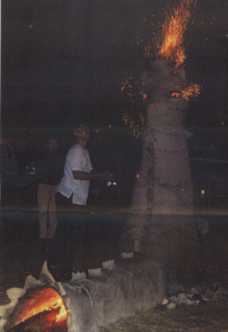

The dragon 'Yoko' at the height of the fire |

|

In I99I I moved to Japan, working as a potter and once demonstrating

my fired earth constructions to the Japanese public. I live

in Tokoname, a small town with a I000 year tradition in ceramics,

situated in central Japan, a gem among the pottery centres

of Japan. Early in I996 I heard. about a local festival in

the neighbouring town of Ono which featured the dragon as a

symbol of festivities. I had, by that time, met Kyoko Inoue,

one of the persons involved in the Festival Committee, and

I proposed to her the idea of constructing a dragon for the

festival. Finding it difficult to have my work accepted for

major art shows and festivals, I saw the Ono Dragon Festival

as a chance of proving my capabilities in this field. More

than a year later my proposal was allowed to enter the arena

of open public discussion and with a sponsor, extensive documentation

and a video of past events, they agreed to my proposal. At

last, I felt, I could do some of this work in Japan.

The building and firing was the least of my worries... until

I began to try and track down the material necessary for my

work. Normally I use adobes which are unfired sun dried clay

blocks made from a mixture of roughly sieved unrefined local

clays with a clay content as low as 40 per cent and mixed with

chopped straw. |

In England I had changed to unfired bricks as

a substitute but, in Japan, finding the type of bricks needed

for the work was difficult, and what was available was expensive.

My budget didn't allow it. It was then that I read the article 'More on

Paperclay' by Graham Hay published in CeramicsTECHNICAL No 3. I was

assured by the Ono Festival Committee that there was no shortage

of suppliers of paper pulp. After numerous phone calls, discovering

the close network between paper manufacturers, it was arranged that

I contact Daishowa Seiishi Paper Company which turned out to be in

nearby Fuji and would we kindly come and collect what we needed.

In the meantime I had been doing tests in my workshop with

newspaper, cardboard and compressed pulp but these proved fairly

unsatisfactory

due to the length of time needed to convert the material into pulp.

The compressed pulp came in sheets and needed to be broken down.

Eventually I made a soup like mixture which gave me something to

go on. Armed with this information and a van stuffed full of bags

of paper pulp, I drove to the clay company to prepare the paperclay.

Applying the finishing touches to the paperclay dragon |

|

Convincing the boss at the clay company was another story but

he was sufficiently intrigued by the whole thing to want to try

it out. We found that breaking down the pulp into a soup like

consistency and then adding the dry clay was going to be time

consuming and we didn't have the facilities to dry out the paperclay

mixture to the consistency ready to use. So, the paper pulp in

the form it was in (lumpy and which could be picked up in handfuls)

was mixed with slightly moistened clay. If squeezed in the hand

it would form a ball but could be easily broken up. The mix proportion

was four parts paper pulp, six parts clay and one part grog.

The mixture was blended by hand and then pugged. We prepared

one ton of paperclay this way. The paperclay when ready to use

had a water content of 38 per cent.

A small model of the dragon

was made and fired with a blow torch by Nakano, the head

of the clay company. He applied an oxy acetelyne torch directly

to the

construction and took it to I300'C in about 30 seconds. To

my relief nothing untoward happened.

Finding a name for the dragon wasn't difficult. With the town's

name of Ono, no other name fitted quite so well as 'Yoko' |

A week before the festival, we started work, building

a supporting framework out of split bamboo and applying the paperclay

directly on the support. We discovered that while the bamboo structure

worked for the tail of the dragon, it was totally inadequate for

the body and we abandoned the idea during construction inclining

towards the more simple and direct coiling approach. A strong typhoon

and heavy torrential rain didn't help and because we had a deadline

to meet in order to be able to finish in time, a fire was lit inside

the body to dry out and strengthen it at the same time. In three

days we had Yoko finished and ready for firing although the clay

was far from dry; that would have required two more weeks at the

least.

Atsuko Ito adds some further decoration to the ton weight

dragon made of paperclay |

|

We started firing around six in the morning and by about

six in the evening Yoko was behaving like a dragon coughing

up, belching out, spewing forth and bellowing smoke, sparks

and tongues of flame. Waste wood was used for the firing but

any wood with a high resin content is suitable because what

is wanted is flame rather than heat.

As the Yoko dragon was for demonstration and effect we only

fired her on the inside. On the whole, given the adverse working

environment and lack of time, the paperclay stood up well.

We pushed it to the limits Cracking was a problem but I feel

this can be solved by introducing internal supports for additional

strength and drying out the piece more thoroughly before firing.

This style of performance clay unites several aspects inherent

in the ceramic process clay, forming and fire. Fire becomes part

of the whole and is not only a tool to convert clay into ceramics.

The kiln, too, becomes a ceramic object a piece of sculpture

totally true to the elements of what it is composed.

I am now

working on a larger scale, free from the restrictions of

kiln size as well as dealing with a new concept - ceramics in the

realm of the ephemeral. |

For more information on Workshops available contact Wali Hawes :

|

|